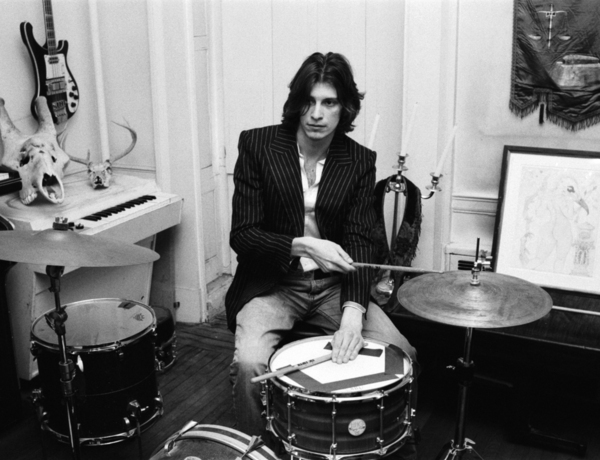

Interview with Noriko Okaku

Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

I spent all my university years in London, where I completed a BA in Fine Art Media and an MA in Animation at the RCA. Following graduation, I worked at a design firm in Tokyo between 2006 and 2008. I then returned to London, where I began working as a freelance animation director. Around 2015, I started expanding my mediums of expression beyond animation to include physical objects and performance, and I now create installations incorporating AI and VR.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I had the opportunity to spend a longer time in Japan, which allowed me to connect with people in the Japanese art scene. These connections led to an increase in projects in Japan, and as a result, I now live a dual-base lifestyle, go back and forth between Japan and the UK.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Kyoto near the Kamo River and the Imperial Palace in Kyoto until the age of 20.

Why and when did you move to London?

When I was majoring in English literature at a university in Kyoto, I tried imagining my future. Graduating, getting a job, getting married, raising children, buying a house in the countryside, and paying off the mortgage—this seemed like one possible path to happiness. However, I felt there might be another path for me. Around that time, I was reading various creative magazines and noticed that the people I admired were all based in London. I had a strong intuition: ‘London is calling me.’ With that, I decided to leave university, study art in London, and moved there at the age of 20.

What initially inspired you to pursue a career in art and animation?

When I was a highschool student, I loved watching music videos from the 90s and early 2000s. I was fascinated by the way music videos conveyed stories in such a short span of time, using only rhythm and visuals, without any dialogue. This form of expression inspired me to dream of becoming a music video director. This was the beginning of me finding myself, realising that I am interested in media. During my university years in Kyoto, I joined a photography club, but I felt limited in conveying my ideas through a single still image, so I often used series of photographs when presenting my work. (Looking back, I think this indicate my potential as an animator.)

After moving to London, I also tried creating video art, but due to my shy nature, I struggled with controlling the subjects, and found it difficult to express my vision as I intended.

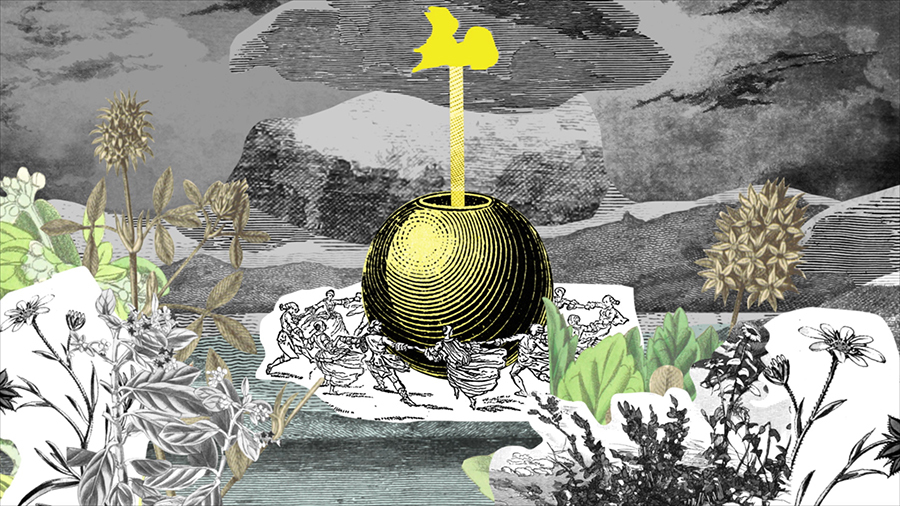

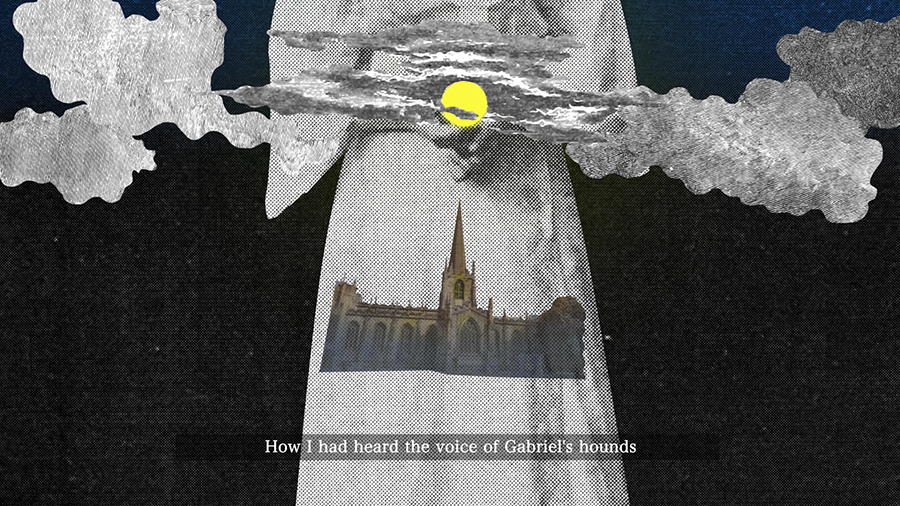

It was then that I discovered stop-frame collage animation. With these techniques, I could move the materials by hand, allowing me to infuse my intentions into the details and faithfully bring my vision to life. Additionally, I intentionally left space in the works to let the audience interpret and create their own stories. I believe this approach has common elements with the music videos I once admired.

Now, I work not only with animation but also with installations and performances, it seems my mediums keeps changing. However, my consistent goal is to create opportunities for viewers to recognise their own perspectives and affirm their sense of self. Through my creations, I aim to convey that the world is made up of diverse viewpoints, hoping that this will lead to a sense of freedom and discovery within each of us. By the way, I have once realised that these actions might have been a response to my unconscious self-denial, stemming from feeling 'different' from others since childhood.

How would you describe your creative process?

It may sound abstract, but I believe the seeds of my ideas often come from small moments of friction in everyday life. By ‘friction,’ I don’t mean arguments or conflicts; rather, I mean the act of ‘doing things’ itself. For example, when I read a book and gain new knowledge, when I talk with friends and realise we have differing opinions, or when I drink water and find it delicious—these moments of awarenss are where the seeds of ideas are born. When I gather what may seem like unrelated seeds, I start to see common threads within them. The commonality I discover then becomes my inspiration. From this inspiration, I expand on the imagery, which is at the core of my creative process.

How does living and working in Kyoto compare to London?

Kyoto is the city where I grew up, so I find myself very relaxing compare to London. I don’t feel the need to go out often to ‘find something new’. I enjoy spending most of my time in my Kyoto studio. I have the studio in central Kyoto, there are several basic cheap cafe places (not a fancy one!) around, which I like as I can stay for a long time, relax, and read. I don’t particularly go out often to see people in Kyoto as I have friends in Japan but they live in different places across the country - I see them occasionally when I travel. Whereas London, most of my friends live in London. So I have more chance to see them and meet new people through them. I can see myself that I am slightly active in London than me in Kyoto.

Do you think working and living in different cities has shaped your style and approach?

As a creative, the only cities I’ve truly lived in are Kyoto and London. (I did live in Tokyo, but I was working at a very busy company and spent most of my time there—I didn’t have much opportunity to explore the city. However, I did acquire valuable computer skills that now support my creative work.) I tend to lead a rather reclusive life regardless of where I am, so I might initially say that the city itself doesn’t affect me much. However, I do feel the unique energy and atmosphere of each place. When I’m in the UK, British ways of thinking naturally shape my daily life, and when I’m in Japan, I find myself immersed in Japanese customs and culture.

Since I travel between Japan and the UK about twice a year, staying for several months at a time, I’ve developed a habit of comparing the two cultures. Reflecting on these differences and similarities often leads to new insights. In that sense, I’m in a unique position to quickly notice and draw inspiration from the distinct cultural characteristics of each city—something that might go unnoticed if I stayed in one place for too long.

Even the act of switching between two languages, English and Japanese, creates fascinating opportunities to explore cultural and linguistic differences. These explorations frequently spark inspiration, which inevitably configures my work.

What do you struggle with the most in terms of working and living in a city like Kyoto?

I don’t particularly feel any struggles, but if I had to mention one, it would be that while Kyoto functions exceptionally well as a tourist destination, its creative scene can feel somewhat limited in scale. That said, I’ve only been back in Kyoto for about two years, so I may still have much to discover about the city’s unique charm and creative potential.

The responsibility of the council in every city is to provide a solid foundation of design, art and cultural facilities, is that still evident in Kyoto?

And how does it compare to London?

Kyoto, once the capital of Japan, retains many temples and traditions, making it an ideal place for learning about Japanese culture and fostering cultural discussions. Additionally, Kyoto is home to many art universities, and I see graduates staying in the city to continue their activities. This provides artists with the advantage of having their school nearby and a convenient environment for building networks.

When it comes to council support, I have an impression that they prefers to support traditional performing arts rather than contemporary art. However, with the relocation of the Agency for Cultural Affairs to Kyoto and international galleries opening branches in the city alongside Tokyo, I feel that Kyoto is the second most significant city for art in Japan. Kyoto shows a strong determination to become more international while preserving its traditional culture. Particularly, with institutions like the Institut Francais and the Goethe-Institut having bases in Kyoto, it plays a vital role as a place that welcomes international artists.

On the other hand, compared to London, there may be fewer opportunities for artists in Kyoto. However, the lower cost of living in Kyoto might allow artists to take advantage of that benefit to find opportunities to present their work.

Do you think it is also the responsibility of the artist/creative to improve the quality of people's lives in their city?

When I hear the term ‘quality of life,’ I tend to focus more on the mental and spiritual aspects rather than the material ones. As someone who moves between countries, I don’t limit my thinking to just the city or area around me. For example, I explore the differences and commonalities between Western and Eastern cultures, and I delve into philosophical questions such as what human happiness truly is. These thoughts may seem broad and abstract, but I believe that this way of thinking aligns with the original concept of ‘quality of life.’

However, even with the broad perspective, I feel that if I am not happy, those around me cannot be happy either. So, I think it is important to first take responsibility for my own work and present something genuine. The reason I believe this is because an artist, by presenting their unique vision, can offer society new perspectives and ways of thinking, inspire others, raise awareness, encourage discussions, and have the power to improve collective well-being. Ultimately, I believe this can contribute to enhancing the ‘quality of life’ in my own city.

Can you tell us about any current or future projects that you are particularly excited about?

I will be participating in an artist-in-residence program in Ibaraki City, Osaka, throughout the year. The residency focuses on the theme of 'Ecology.' What’s interesting is that I am an artist who has recently worked with VR and AI technology, which might seem to be in opposition to ecology and nature. It seems that the curator chose me because they are interested in how these seemingly opposing elements will create a chemical reaction. As it appears that there is no inevitable way for humans to live without technology, it is important to consider how we can coexist harmoniously with it.

If we view nature as part of a larger whole, then the technologies developed by humans can also be seen as part of nature. In my previous work, I incorporated VR and technology into the concept of Yaoyorozu, a Japanese Shinto belief system that worships nature. I am excited about the opportunity to further develop this approach during the residency and look forward to the possibilities ahead.

Noriko Okaku - mixtape

These soundtracks were generated as part of the exhibition held at Towada Art Center Satellite Space from July 6 to September 8, 2024. AI generated these tracks by incorporating the names of visitors into text, transforming them into songs. Over 1,700 tracks were created during the two-month exhibition period, and this platform features a curated playlist of 19 selected tracks.

If you could add or change something about Kyoto, what would that be?

Nothing in particular. Even Kyoto is known as a city of tradition, it has already changed a lot compared to 100 years ago, and I believe it will continue to evolve over time. I hope that Kyoto doesn't become constrained by tradition, but instead transforms into a city that embraces change, with a sense of renewal and circulation—like the flow of water in a pond, not relying on stagnation. I hope the city continues to adapt while maintaining its unique identity.

What would be your dream project?

Last year, I did a lecture performance for the first time, and I found it incredibly interesting. I’d like to create a lecture performance series that explores ‘language’.

If you could choose any artist/creative to collaborate with, who would that be and why?

I don’t have any specific ideas at the moment. Since I’m interested in symbols (visuals) and language (sounds), perhaps something related to music? It would be interesting to have someone to talk about these things with.

What do you do to switch off?

Take a bath. A long soak.

What does home mean to you?

My home in London serves as a place where people can gather and feel at ease. Meanwhile, my house in Kyoto functions as a studio and feels more like a storage space for my works. However, since I enjoy living a nomadic lifestyle, I may not fully embrace the concept of a ‘home’ to return to. Instead, I feel as though I myself embody the idea of mobile ‘home.’

Describe the perfect day for you in Kyoto.

It’s a pretty simple answer - I feel perfect when I have time to take a break at the cheap café in the neighbourhood, read a book, and come up with new ideas. Going back home, writing ideas on the wall (In my Kyoto home, I’ve covered the walls with large sheets of papers, allowing me to write directly on them.) Then, I take a long bath and go to sleep. Writing down freely on the wall process is so much fun as it progresses. Having a day like that makes me feel it’s a great day. Right now, I’m in London, but I miss the wallpaper in my room.

Sometimes people relate a specific smell to the city they live in or the place they grew up, does Kyoto evoke a personal smell to you?

Maybe the smell of incense burned in temples? Also, the scent of tatami.

If you could choose any city to live in, where would that be, and why?

At this moment, I have a nomadic nature, so I don't have a particular city I dream of settling in. However, it would be wonderful if I could visit various countries and live in each town for a certain amount of time, traveling around the world and moving on to the next city.

kyoto by Noriko Okaku

A personal view of Kyoto by visual artist and animator, Noriko Okaku. See Noriko's citylikeyou profile page here.

More Interviews